Software 2.0: Code is Cheap, Good Taste is Not

The rules of software development are changing.

- What is Software 2.0?

- Who is This For?

- Software 2.0 is Not “Vibe Coding”

- Goals of Software 2.0

- Requirements of Software 2.0

- Software 2.0 Process Overview

- Conclusion

I’ve been using LLMs to help me develop software in earnest since the original releases of GitHub CoPilot.

The earliest talk I gave on the subject was in March / April 2024 to a customer who was interested in rolling out LLM-assisted coding to their staff. I made a public-facing version of this talk in July, 2024. All of those techniques are still fundamentally useful, but the tooling and models are simply lightyears ahead of what they were then.

Things are moving very quickly in the LLM-assisted coding space, leading many to ask “is this the end of the line for human software developers?”

The “short” answer to this question is:

- There are classes of human software developers who are already rendered obsolete by LLM-assisted coding tools and it’s only a matter of time before bureaucratic and market inertia catches up to either eliminate their roles or compress their wages. We are going to call these developers who steadfastly refuse to learn LLM-assisted techniques “coasters1” going forward;

- Developers and designers who escape “coaster”-ism through learning how to wield LLMs effectively, skeptically, and cautiously are going to be more productive and needed than ever before; because

- LLMs have fundamental limitations that will likely never be resolved with transformer architectures, despite advances in both techniques and hardware. These are irresolvable issues with the mathematics of LLMs, verifiability of output, scaling laws of AI, and design trade-offs that AI labs have explicitly chosen with transformer architectures.

In the longer text of this essay, I want to explore these questions and others in more depth.

In addition to addressing the current and future state of the software industry, I also want to introduce some techniques for leveraging LLMs correctly - not merely prompting, but through treating LLMs like programmable virtual machines that can be used in ways that were not possible with Software 1.0 engineering tools.

I hope you find this helpful and insightful.

What is Software 2.0?

Software 1.0 is the era from Charles Babbage up until 2021 or so - when GitHub CoPilot was first made available in preview.

Summing up a century and a half of computer science into a single pull-quote:

Software 1.0 is software you specify.

The labor of software engineering revolved largely around choosing technologies and specifying how they’re to be used through one’s code.

For instance, if I wanted to build a new user onboarding wizard for a SaaS product, I might start specifying some CSS styles like so:

<style>

/* Wizard steps styling */

.wizard-steps {

display: flex;

justify-content: center;

gap: 2rem;

margin-bottom: 2rem;

}

.wizard-step {

display: flex;

align-items: center;

gap: 0.5rem;

color: var(--tf-stone);

}

.wizard-step.active {

color: var(--tf-steel);

}

/* etc... */

</style>

I’m making all the choices.

- I’m composing the CSS class.

- I’m choosing the colors.

- I’m defining variables where colors might need to change depending upon the user’s progression through the wizard.

- If I wanted to use a CSS framework instead, I might just need to pass some variables into a Tailwind or Bootstrap component instead.

This is “normal” programming - programmers writing specific instructions with code.

What then is “Software 2.0?”

Software 2.0 is software you verify.

In software 2.0 we’re not writing every line of code by hand - we’re delegating most of that decision making to an LLM-powered agent that is proficient at writing software:

You are an expert in front-end web design: HTML, CSS, and are

familiar with popular CSS and JavaScript frameworks.

I would like you to create a static HTML mock-up of an onboarding

wizard where a new user has to select their email account, folders

they wish to sync, their billing plan (which should kick out to

Stripe Checkout and return back after a completed purchase), their

retention period (gated by the plan type they choose in the previous

step - please see @docs/billing/plans.md for reference), and then a

confirmation screen. Once the user clicks "confirm" on the

confirmation screen, please show a progress bar with status updates

indicating sync progress - you can fake this using some CSS or JS

animations.

Make sure you do the following:

1. Integrate this mock-up with our existing

@docs/design/app-mockup.html so the flow feels clickable

2. Follow our brand guidelines for color / logo choice:

@docs/design/brand-guidelines.md

3. Write out an implementation plan for implementing this mockup in

the real application, described using the real source styles and

JS inside @src/wwwroot

I’m telling Claude Code or Codex or whatever what I want and offer a handful of guidelines on how it’s to be done:

- Use the same colors we’ve chosen for everything else;

- Integrate with the existing mock-up so the onboarding wizard coheres with everything else;

- Provide instructions on how to integrate this with the production application, as its tech stack is likely different; and

- Specify the steps that need to be taken inside the wizard itself.

If I were a talented graphic designer, I could just hand over a full-size image of what I wanted and tell the LLM “render this for me in static HTML” and that would probably work too - at least for multimodal large language models like Claude or ChatGPT.

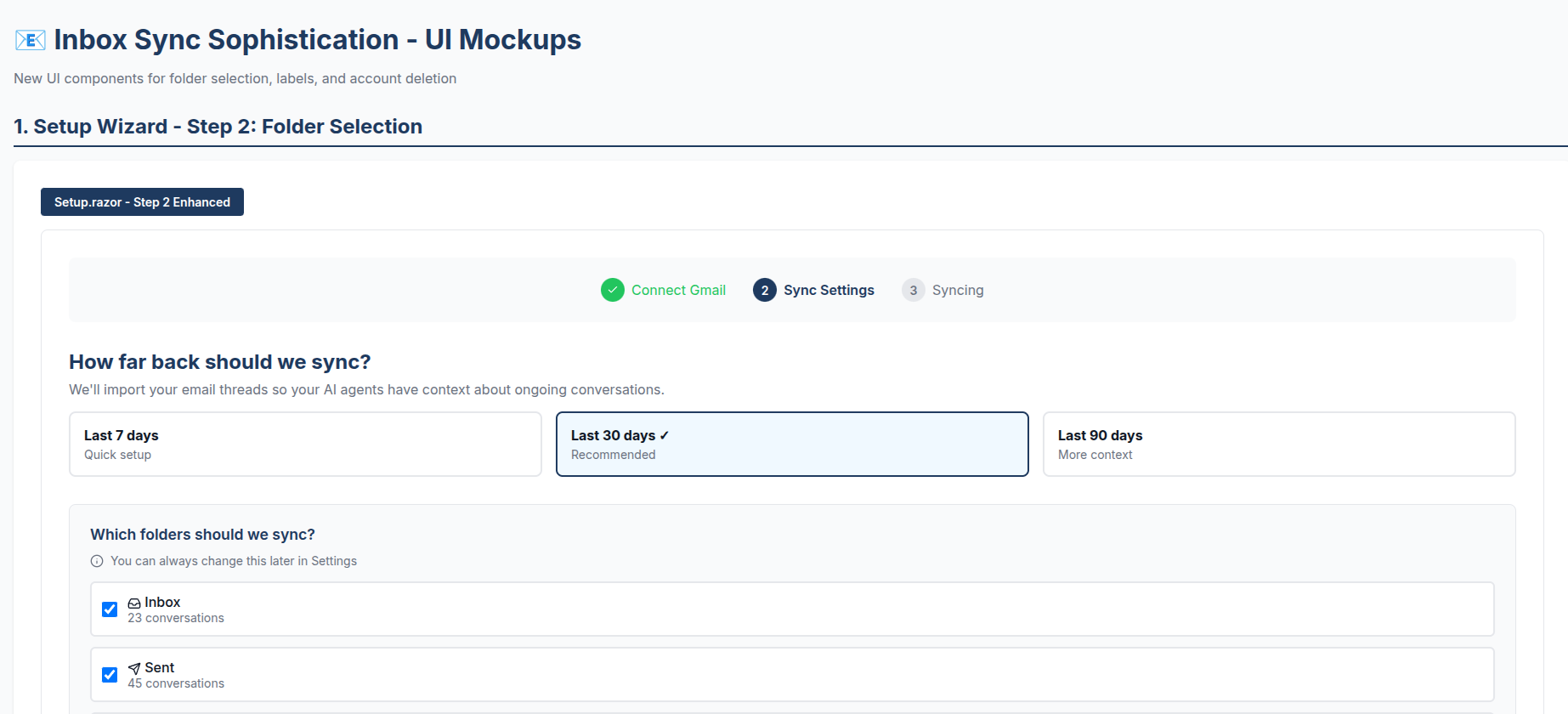

In less than 5 minutes, I will have a fully functioning onboarding wizard - here’s what my actual mockup, made for TextForge looked like:

My original prompt didn’t have some of the detail the one above has - we hadn’t integrated Stripe yet, for instance. I had Claude Code create this so I could visualize how selective folder sync, a dynamic and detail-rich UI element, might look when presented to a user. I thought this was acceptable, although it didn’t do everything just right - the logo is wrong for instance.

The obvious and clear reason why we’re discussing LLMs is that Software 2.0 yields output multiple orders of magnitude more quickly than Software 1.0.

Companies that write software want the tremendous output increase, but that increase is not without risk: does anyone know what this code does and how it works?

Who is This For?

I’m writing essays under the umbrella of “Software 2.0” for two audiences:

- Software developers who want to achieve more with LLMs but aren’t sure how - my hope is that through reading about Software 2.0, you will find and discover a repeatable, systematic method that works for you. In so doing, this method allows you to experience the joy of creation through using AI to help you do more, learn more, and create more personally and professionally.

- Software product owners and leaders who are seeking to help their team get more done with LLMs - members of your organization above, below, and around you might all be skeptical about what large language models can help you and your organizations accomplish. I hope to arm you with processes, techniques, and tools that will help you transform skeptics into converts.

Software developer wage compression is real and is already happening2, and we’ll address that directly in a future essay. If someone wielding LLMs effectively produces 30x the output of someone who doesn’t, the math is not going to resolve itself in the coaster’s favor.

But the flip side is equally true: these skills are in enormous demand right now and the supply of people who have them is thin. Developers who invest in learning Software 2.0 techniques today are in a seller’s market. That window won’t stay open forever. Once these skills become the accepted baseline, not having them won’t just compress your wages - it will eliminate your position.

This isn’t another essay telling you that software engineering is “solved” and you should be afraid. Software 2.0 is a process, not a prophecy - and it’s about having fun shipping great software that users love, faster and cheaper than ever before. But it is not free. There’s considerable work, trial-and-error, costs, and “risk” taking involved. I don’t really think it’s “risk” - but you have to get far enough down the LLM adoption curve to start seeing it that way.

Software 2.0 is Not “Vibe Coding”

Software 2.0 is not “vibe coding” - it is process-driven engineering using LLMs as the primary change agents inside the software development lifecycle.

Software 2.0 requires discipline, monitoring, experimentation, and constant process improvement to work at business-scale.

This process involves:

- Learning how to appropriately leverage different large language models and harnesses (Claude Code, OpenCode, etc) for different workloads;

- Managing context in order to maximize agent yield and alignment with your goals;

- Structuring implementation plans, specifications, and other “project context” elements into agent-friendly formats that can be fed into context;

- Improving agent alignment through authoring of skills, internal tools, MCP servers, and other tools big and small;

- Improving code quality and structure so agents have an easier time falling into the “pit of success” when working on your code; and

- MOST IMPORTANTLY: investing in comprehensive verification processes that help spot LLM errors and steer it in the right direction.

Software 2.0 will not help you “one-shot” an application, but it will help you understand how LLMs work and use them effectively to deliver better software.

Goals of Software 2.0

The goals of this process are:

Marginalize Software Development Opportunity Costs

Every software team carries technical debt34 - regrettable decisions from the past that tax every future change. There’s usually a backlog of things everyone knows should be fixed but can’t justify the engineering investment: the billing system that’s too coupled to one payment provider, the N+1 query pattern baked into every page load, the zero-test-coverage codebase where changes are an act of faith.

LLMs fundamentally change the math on paying down that debt.

We experienced this firsthand on Sdkbin, where the original developer had coupled our entire billing system to Stripe so tightly that supporting purchase orders - something our customers increasingly needed - was prohibitively expensive to add. For five years we worked around it with manual processes, because the cost of fixing it outweighed the benefit.

LLMs changed that calculus in early 2025. We started attacking the lower-hanging fruit: simplifying Byzantine query patterns that looped through multiple EF Core calls per page request into clean, single-service-call architectures. I designed the pattern and implemented the first couple by hand; LLMs executed the dozens of remaining transformations over several months. Specifically, LLMs helped us:

- Understand legacy code none of us wrote - how it worked, how it used third-party dependencies, and where its opaque configuration originated. Days of investigative work compressed into minutes.

- Create a repeatable playbook for transforming the legacy system into the streamlined one - a pattern we could trust the LLM to execute repeatedly.

- Execute the playbook and add tests as it went - Sdkbin had zero effective test coverage when I started. Now we have ~50-60% coverage and climbing, much of it LLM-authored.

We’re almost done deploying the modernized billing system too - putting an end to a five years’ long source of embarrassment for me. LLMs made it possible to pursue all of this without pulling too many resources away from our day jobs.

That’s the first goal of Software 2.0: marginalize the costs of software development.

This makes it easier for software development teams to:

- Change their minds - not happy that our billing API was coupled to Stripe to a ridiculous degree? Let’s ask Codex or Claude for some strategies on how to uncouple that without losing data or disrupting ongoing billing.

- Experiment with new approaches and technologies - want to see if we can improve latency on our front-end by migrating to HTTP Server-Sent Events (SSE) instead of client-side polling? Have the LLM run an A/B test against control vs. experiment and report back with problem areas and opportunities.

- Freely invest in “off the hot path” / “side projects” that might yield benefits later - if we want to build some in-house tooling to solve a common, recurring problem, we don’t have to sideline virtually any critical path work to engage an LLM in prototyping one of these. Exploring ideas becomes an asynchronous task largely carried out for us by a large language model. Productionizing those ideas is a different story.

Radically Accelerate Time to Market

The most obvious benefit of Software 2.0 over 1.0 is accelerating time-to-market: deliver value more quickly to customers with fewer human-hours.

LLM-assisted coding compresses the time horizons of most stages of the software development lifecycle.

Consider a common class of problem: you have a tricky cross-cutting concern where there’s no single obvious solution, and each candidate approach involves different trade-offs. A human developer would research one approach, prototype it, hit a wall, backtrack, and try the next. Days of sequential exploration for a problem that might have three viable solutions.

LLMs let you explore all of those approaches simultaneously.

We recently hit exactly this situation in Akka.NET: correlating log events with OpenTelemetry traces. Akka.NET processes logs asynchronously through actor message passing, which means Activity.Current - the ambient context that OpenTelemetry uses to correlate logs with traces - is always null by the time a log event reaches the actual logging backend. There’s no straightforward way to thread that context through using Akka.NET’s built-in logging infrastructure.

Using OpenProse - a programming language for orchestrating multi-agent AI workflows - we were able to have three agents build parallel proofs of concept with objective pass/fail goals, then have the results reviewed and ranked automatically5:

agent architect:

model: opus

persist: true

prompt: "Senior .NET architect. Designs solutions, never codes."

agent implementer:

model: sonnet

prompt: "Expert C# developer. Akka.NET and OpenTelemetry."

agent reviewer:

model: sonnet

prompt: "Code reviewer. .NET performance and thread safety."

# Architect proposes 3 solution paths

let analysis = session: architect

prompt: "Akka.NET logs asynchronously - Activity.Current is null

by the time logs hit the backend. Propose 3 solutions."

# Implement all three in parallel

parallel (on-fail: "continue"):

path_a = session: implementer

prompt: "Path A: capture Activity at callsite, swap

Activity.Current at the logging endpoint."

context: analysis

path_b = session: implementer

prompt: "Path B: custom OTEL LogProcessor with

correlation IDs in a concurrent dictionary."

context: analysis

path_c = session: implementer

prompt: "Path C: attach TraceId/SpanId as structured

log properties, use Serilog enrichment."

context: analysis

# Review all implementations in parallel

parallel:

review_a = session: reviewer

context: path_a

review_b = session: reviewer

context: path_b

review_c = session: reviewer

context: path_c

# Architect ranks all paths and recommends the best

output recommendation = resume: architect

prompt: "Rank all 3 on: correctness, performance,

compatibility, simplicity, OTEL compliance. Pick one."

context: { path_a, review_a, path_b, review_b,

path_c, review_c }

The first batch of proofs-of-concept the agents generated weren’t good. I re-prompted it with feedback and OpenProse adjusted itself, running a second batch.

That iteration produced another set of proofs of concepts, one of which is exactly the approach we shipped across two repositories. In Akka.NET v1.5.59, we captured the ActivityContext struct at log event creation time - before the mailbox crossing destroys Activity.Current - and carried it as a property on the LogEvent record (Path C). Then in Akka.Hosting v1.5.60, a custom BaseProcessor<LogRecord> called AkkaTraceContextProcessor extracts the trace context from the log state and sets it on the LogRecord for OpenTelemetry exporters (Path B).

The whole workflow ran in about 45 minutes, including waiting for me to review the results the first time around. A human investigating these three approaches sequentially would have spent days researching and testing each of these.

Other types of time-to-market saving activities:

- Using agent parallelism to look for specific bugs and defects in production software - this technique is especially popular in the security scanning / vulnerability6 space right now.

- Prototyping delightful UI/UX workflows - quickly synthesize and re-work static mock-ups in a single sitting. Even graphic designers and UX people would love to take their own work and play with it interactively before handing it over for implementation. LLMs make this inexpensive for them to do independently without the assistance of human software developers.

- Freedom from drudgery and toil - no one is going to miss editing YAML by hand for constructing Azure DevOps and GitHub Actions pipelines. There are endless examples of incidental complexity7 like this that consume the time of highly paid engineers without building transferable skill or improving system quality.

This is by no means an exhaustive list. Software 2.0 makes any activity that can be reliably carried out by invoking local and remote functions amenable to automation and parallelization.

Scale the Productive Output of Human Team Members

The elephant in the room: “is AI going to replace developers / designers / devops engineers / etc?”

I’ll dedicate plenty of ink on that subject in a future essay, but let me direct you to an interesting observation from this past week’s Atlassian (the makers of Jira and other popular software development products) earnings call transcript - emphasis mine:

AI Impact on Customer Expansion – Companies using AI code generation create 5% more Jira tasks, see 5% higher Jira monthly active users, and expand seats for Jira 5% faster than non-AI users within the software segment.

This doesn’t read like companies paring their engineering departments down to the nubs and replacing them with LLMs - this reads like headcount and output scaling with LLM usage. Now why would this be the case, contra the “software engineering is solved [by AI]?” memes you frequently see on X, LinkedIn, and elsewhere?

Because the business of shipping software is still the business of details. Details are what separate your vision from everyone else’s. Details are what win human customers. Details are taste - and Large Language Models don’t come with good taste. This is why “AI” and “slop” are correlated in our zeitgeist: output is cheap, taste is not.

Software 2.0 seeks to empower the people who work with LLMs to explore more ideas, learn more, do more, and try more.

Conserve Software Quality, Security, and Performance

Everything written about Software 2.0 in this essay so far has spoken to what LLMs do well.

Large language models alone can’t deliver Software 2.0, for the following reasons, even with ambitious projections for future scaling:

- Hallucinations - happen because the LLMs predict what sounds plausible, not what’s been verified as true. This is a function of mathematics and there is no “solve” for it - other than a subject we’ll be talking about at-length: “verification!”

- Finite context - “context windows,” the set of input and previous output tokens “in-use” by an LLM to predict the next output tokens, have a finite effective size that correlates to a combination of factors such as model architecture, parameterization, and hardware constraints. More importantly, the maximum advertised context window is not the same as the context the model can reliably use8. In other words, large context windows are an I/O capability, not a guarantee of comprehension.

- Misalignment – all models have innate biases as a result of their training, and allowing these biases to run unchecked will often produce unintended consequences. Even when an LLM is operating within its effective context window and is not hallucinating, its default behavior may still diverge from system goals. This can manifest in subtle ways such as: not choosing your preferred technology stack or severe ones like generating insecure code. Learning how to prompt effectively and how to constrain models using agent harnesses (e.g., Claude Code) can mitigate these issues, but doing so introduces real complexity and ongoing cost. It is not “free” and not solved by improved models in the future.

The thrust here is that while LLMs are improving at an impressive pace they are constrained by hardware, design, cost, and more. Software 2.0 works within these constraints to wield them effectively.

Requirements of Software 2.0

Software 2.0 is not free or instant - it is a process that takes experimentation, patience, discipline, and a willingness to make and learn from mistakes. But if you follow the process, you will see results.

Here is what you need to get started with Software 2.0:

Table Stakes

- Tokens - you need to purchase either dedicated hardware (GPUs) to run your own local models or get a subscription to GitHub CoPilot, OpenAI Codex, Claude Code, OpenRouter, Groq, or dozens of other inference providers. Claude Code MAX at $200 per month is extremely cost-effective for most production use, but experiment with different models and see what suits you best.

- An Agent Harness - some means of allowing large language models to make local tool calls (reading and editing files; invoking the shell; browsing the Internet; and more), fetch local context, communicate with a remotely-hosted LLM, transform the output tokens into tool calls. I use Claude Code and OpenCode.

- Continuous Integration and Deployment - if you are in a business with no automated tests and no way of pricing-in risk regularly via small deployments, you don’t have a business structure that can properly de-risk LLM output. Fix this first.

- Issue Tracking and Documentation - this is your context input system for agents. If you don’t have any written documentation for your application, you are going to start producing some as part of establishing the “project context” agents need to be effective. Committing markdown files directly into your source code repository actually works pretty well for this.

- Distributed Source Control - specifically distributed, not just “source control.” Software 2.0 requires the ability to have multiple agents working across the same repository in parallel branches - something centralized systems like SVN or Team Foundation Services fundamentally cannot support.

git worktreeis an especially useful feature for this: it lets you check out multiple branches simultaneously without cloning the repository multiple times. - Agent-Accessible CLI and MCP Tools - agents are only as capable as the tools they can invoke.

ghto access GitHub, the Playwright MCP server for browser automation, and others. The richer your agent’s toolbox, the more it can accomplish without human intervention.

Once you have all of this in-place, you can get started.

Nice to Have

Some other tools that will make your company’s experience working with LLMs even better:

- Speech-to-Text Software - you won’t believe me until you try this yourself, but not having to type every single prompt will greatly accelerate your ability to work quickly with LLMs. Invest in a good piece of Speech-to-Text software to help you achieve this. I created and use witticism, but other off-the-shelf products out there are probably better, such as Handy.

- Shared Agent Memory Server - a shameless plug, but I get a ton of mileage out of using Memorizer MCP to transfer memories between team members / agents running on different machines. I recommend using that as you become more comfortable working with LLM coding tools.

- Read-Only Access to Your In-House Data and Infrastructure - having Claude invoke

kubectlto fetch K8s logs saves me hours and hours of troubleshooting time. If you’re worried about the agents doing anything risky, lock down their access like you would any human employee and restrict them to read-only access. That way any mutation to data or infrastructure has to pass through a human approval layer first.

If you’re worried about giving LLMs access to your data or source code, you can always go the route of self-hosting local models. That will make things somewhat more challenging because they have very high memory requirements in order to be competitive with state of the art models like Codex or Opus, but you can still get great results applying Software 2.0 to a model like Qwen3-Coder-Next or Qwen3-Coder-30B. Your mileage may vary.

Software 2.0 Process Overview

We’ll get into each of these areas in more detail in a future essay, but these are the essential elements of the Software 2.0 process.

Automated Verification of Large Language Model Output

“Software 2.0 is software you verify” - so what does that mean exactly? We’ll get into the non-determinism of LLMs later, but for now all you need to know is that LLM reasoning is imprecise.

Delegating a task like building an onboarding wizard is quite analogous to delegating that same task to another human on your team - you have to accept, to some degree, that person’s tastes, experience, and way of doing things when you give them the responsibility.

In any engineering organization, all individual output has to be run through a quality control process - this is “verification:”

- Other team members review and comment on designs or pull requests;

- Automated quality checks like the compiler, linters, are run against the source;

- Automated test suites are run; and

- Work might be run through a security scanner to find CVEs or other changes that violate security policy.

With large language models, this is how we validate their output too - through non-LLM verification tools and human review.

In the case of my onboarding wizard from earlier - I verify it by eye-balling it, interacting with it, and working with the agent to refine it until I accept it.

Once the mock-up has been “accepted” it can be used for pixel-by-pixel verification with the live application UI when I delegate that task to an agent in another future session. My “approved mockup” becomes an artifact the LLM can use for verification in the future.

Scaling Code Verification with Volume

The interesting challenge is: if LLMs scale output so significantly, how can you possibly keep up with the verification burden? The bottleneck here is human-led review.

The answers are:

- Humans aren’t going to review every line - and if you are honest, you’ve likely never reviewed every line of every human-authored piece of code sent across your desk either. This is, largely, an unrealistic standard wielded by LLM-skeptics that absolutely do not apply it to human-authored code in their own organizations. I’ve reviewed thousands of pull requests against Akka.NET and though I try my best, I have limited time and don’t catch every little detail.

- Therefore, we must automate as much QA as possible using non-LLM tools - one of the reasons why statically typed languages are superior for LLM-assisted coding is because their compilers eliminate many classes of errors inside the LLM’s “development loop” just like they do in a human’s development loop. Automated tests, linters, and tools like

dotnet-slopwatchalso fit into this category. - It is possible to have LLMs review each other’s work… But… - “adversarial review” is a technique where 1 LLM reviews another’s work from a different session; it can be very effective provided that the reviewer is given sufficient context in order to understand the authoring agent’s intent. Otherwise, it will flag a ton of false positives - this is why I don’t find tools like CoPilot PR reviews to be all that useful.

Most of what you’re going to need to develop to build a robust verification pipeline will be non-LLM methods, such as:

- Static analysis - compilers, Roslyn Analyzers, formatters, linters, and so on. Anything we can make verifiable via static analysis, we should: it’s the cheapest and fastest way to keep LLMs on-track.

- Automated testing - all manners of test work well here: unit tests, integration tests, acceptance tests, property-based tests, smoke tests, end-to-end tests, and so on. Combine this with automated code quality checks like CRAP Scores to help LLMs attack complexity and low-test-coverage areas of your application.

- Click testing - with the Playwright MCP server or any other form of browser automation, LLMs can drive full-blown click testing of your applications. Combine this with platforms like Aspire9 to make it easy for LLMs to both orchestrate and observe your applications with OpenTelemetry.

- Verification programs - just to give you a simple example of a “verification program,” I use https://github.com/Aaronontheweb/link-validator to validate that all internal / external links in a given application return a

200or equivalent HTTP status code, a simple but effective form of verification for web sites and applications.

Establishing a Helpful System Prompt and Project Context

Every agent harness has you initialize a repository with a CLAUDE.md, AGENTS.md, or similar file. This defines the agent’s “system prompt” - the default instructions it uses each time it starts up inside your repository.

The quality of this file directly determines how well agents perform on first contact with your code. We want to arm agents with helpful context:

CLAUDE.md/AGENTS.md- how should agents interact with this repository? What skills should they use and when? Where can agents find PRDs, ADRs, branding guidelines, mock-ups, and end-user documentation? How should different types of “agent personae” be routed (i.e. UI design and back-end engineering agents might have different starting points.)PROJECT_CONTEXT.md- what does this project do? What are its goals? What other repositories are “adjacent” to it (i.e. a separate Terraform or Pulumi repository used to deploy it.) What phase are we at in the SDLC currently?TOOLING.md- what is our tech stack? How is it deployed? What are the relevant guidelines for working on it?

Start here: if you do nothing else from this essay, write a CLAUDE.md that describes how to build, test, and deploy your project. Tell the agent where to find things and what conventions to follow. This single file will dramatically improve agent performance - and it has the side benefit of finally forcing developers to document things.

Become Effective Planners

One of the biggest hurdles to adopting large language models for most developers is that they will finally have to embrace becoming specification authors and project planners themselves. “Developers will happily spend months coding in order to avoid hours planning” will not survive past 2030 - we’re all planners now.

“Plan mode” is where you are going to spend most of your time as a developer in Software 2.0 - working with your agent to form PRDs, implementation plans, and specifications. There are numerous formal planning frameworks that are AI-friendly, such as OpenSpec that can help make this a highly structured process.

For many developers, working with LLMs and iterating specs and implementations in real-time will feel like the very first time “agile” software development has actually lived up to its promise.

The litmus test for an effective planning session: can the agent execute your spec without asking a single clarifying question? If it has to ask, your spec isn’t specific enough. The goals are:

- Make “what you want the LLM to do” unambiguous enough that your wishes can actually be fulfilled;

- Spell out an implementation plan that helps the LLM understand roughly how it should implement the design;

- Break the implementation plan down into discrete tasks that can be spread across multiple context windows; and

- Provide the LLM with clear instructions on how it can determine if it has successfully completed its assigned tasks - this is where your verification pipeline earns its keep.

Manage Context Windows Effectively

LLMs tend to become less coherent the larger the context window becomes - so a single context window should accomplish a single, well-defined objective. Think of each session the way you think of a good function: it has one job, it does it well, and it finishes.

Good system prompts and effective planning sessions (covered above) are the foundation - they help you start each session with the right context already loaded. Beyond that:

- Write effective prompts that activate the right regions of the LLM weights. Being specific about technologies, patterns, and constraints consistently produces better output than vague instructions.

- Don’t try to do too much in a single session. If you find yourself re-explaining something the agent should already know, your context window is likely degraded. Start a fresh session.

- Use sub-agents to do token-expensive work, parallelism, or grunt work - well-designed agent harnesses will do this automatically, but sometimes you’ll need to give specific instructions (i.e. OpenProse).

- Have agents frequently save their work to the file system or to a tool like Memorizer, so in the event that your context window compacts you can easily “refresh” your current context in a new session.

Leverage Sub-Agents and Cheaper Models

The principle is simple: match model cost to task complexity. Not every task needs your most expensive, most capable model.

One of my favorite sub-agent definitions I’ve synchronized in our team’s environment:

---

name: playwright-gopher

description: Efficient browser automation agent optimized for token-intensive

Playwright operations. Use this agent for web scraping, screenshot capture,

browser navigation, form filling, and UI interaction testing. Designed to

handle expensive browser operations using more cost-effective models while

maintaining quality results.

color: blue

model: haiku

---

Why burn valuable Claude credits having Opus (a complex, sophisticated model) take screenshots of web apps, when I can have Haiku (the smallest, cheapest Claude model) do it instead? This preserves my main context window in Opus AND reduces my token spend.

As agent harnesses mature, more of this routing will happen automatically. But today, learning which models to use for which tasks - and how to compose them into multi-agent workflows - is a meaningful competitive advantage.

Conclusion

Software 1.0 was about building things you could specify. Software 2.0 is about building things you can verify.

This isn’t an extinction event for software developers - it’s a paradigm shift in what software developers do. The work moves from writing every line of code by hand to designing verification systems, managing agent context, planning effectively, and applying taste to the tsunami of output that LLMs produce. The developers who embrace this shift will ship more, learn more, and create more than was ever possible before.

There’s a lot more ground to cover in future essays: building “unattended” agent workflows that run autonomously, enabling agents to self-improve their workflows, observability, evaluating effective prompt and model combinations with tools like DSpy, and more.

But don’t wait for those. You can start today:

- Write a

CLAUDE.mdfor your project - even a basic one that describes how to build and test it. - Pick one verification gap in your workflow and close it - add a linter rule, write a test, set up a static analyzer.

- Take a piece of technical debt you’ve been avoiding and see what an LLM makes of it.

Stop doom-scrolling AI Twitter. Start building software you can actually verify.

Subscribe to receive future Software 2.0 essays via email.

-

in “There Has Never Been a Better Time to be a Junior Developer - And It Won’t Last Forever” I called this class of software developer “slow seniors.” The term “coaster” is an expansion of this category. ↩

-

Much of the current wage pressure predates LLM-assisted coding and is attributable to massive overhiring during the pandemic. As IBM CEO Aravind Krishna put it: “People gorged on employment during the pandemic and the year after” - companies expanded headcount by 30-100% and are now correcting. Had that hiring bubble not occurred, the correction happening now would not be attributable to AI. ↩

-

“DRY Gone Bad: Bespoke Company Frameworks” and “Frameworkism: Senior Software Developers’ Pit of Doom” are both good treatises on technical debt. “Professional Open Source: Maintaining API, Binary, and Wire Compatibility” and “Professional Open Source: Extend-Only Design” are good pieces on specific techniques to limit it. “We’re Rewriting Sdkbin” is a personal horror story about a technical debt inferno I’m still dealing with. ↩

-

I recommend reading “High Optionality Programming: Software Architectures that Reduce Technical Debt - Part 1” and watching part 2: “High Optionality Programming - Techniques.” ↩

-

This is a simplified illustration of an OpenProse program - a real version would include fuller agent prompts, error handling, and more detailed evaluation criteria. Here’s a more realistic version. OpenProse is an open source programming language for orchestrating AI agent sessions. ↩

-

There are tons of commercial offerings in the AI vulnerability scanning space, but also open-weight models like VulnLLM-R: Specialized Reasoning LLM for Vulnerability Detection that you can try yourself. ↩

-

In essence: “yak shaving.” ↩

-

See “Context Is What You Need: The Maximum Effective Context Window for Real-World LLMs” (arXiv:2509.21361). The paper shows that the maximum effective context window (MECW,) the amount of context that actually influences model outputs, is often orders of magnitude smaller than the advertised maximum context window (MCW), and varies significantly by task. In many cases, adding more context degrades performance rather than improving it. ↩