The Necessity of Systematic Thinking

Even smart people peter out in the face of daunting problems.

I spend a lot of my professional time training other software developers on how to build next-generation applications. Distributed and concurrent systems; stream processing; stateful web applications; soft real-time applications; and so forth. Cutting edge stuff for the majority of my industry.

One of the huge advantages of inexperience, such as when you first graduate from school, is your default state of being with the world is one of perpetually learning and adopting new skills and techniques. You’re not intimidated by taking on a project with lots of unknowns because… every project feels that way during the beginning of your career. But once you’ve been in your industry for a few years you pick up a few things: tools, tricks of the trade, techniques, pitfalls, preferences, methodologies, and so forth.

Fast forward to your five, ten, or fifteen year mark in your career you’ll run into what is an existential crisis for most people: a paradigm shift. The experience can different for everyone. It could be:

- Starting a new job at a really small company with tremendously more responsibilities and influence than you did when you were working for BigCo.

- Being promoted from an individual contributor to a manager.

- Taking on ownership of a product, including both the technical and business side of it.

- Working on a much more demanding and critical project.

- Founding a business and suddenly having to care about things like where revenue comes from.

And so forth.

The common thread among all of these experiences, those of my customers, and my own is: much (but never all) of what we’ve spent our past N years in industry learning isn’t going to get us very far in our new endeavors. We are expected to produce at as high or higher levels than we were before while having to learn reams of new skills, technologies, techniques, and practices on the job.

It can be a stressful and scary proposition; I remember what it was like when I embarked on that process for the first time. Things things didn’t go so well initially, but ultimately I figured it out.

If you make it through to the end of this post you’ll walk away with is a loosely structured methodology for how to handle big challenges in a manner that puts you in control of the ship, rather than merely coming and going with the tide.

Conquer Ambiguity with Systematic Thinking

The greatest stressor for most people undertaking a big, ambitious project is usually its lack of formal structure or definition.

The ambiguity of a new role, new job, or the scope of a big project completely terrifies people who’ve grown up through two decades of regimented classes in school with easily quantifiable grades followed by a number of years working as a worker bee for BigCo with semi-defined hierarchies, business processes, project management systems, pay scales, and the trappings of bureaucracy.

A empirical law of all merit-based organizations: the amount of responsibility you are given is inversely proportional to the amount structure1.

The CEO has the least amount of structure, the cashier working in the checkout aisle is given the most.

When you take on an initiative with greater responsibilities, it is your job to create and provide the structure for seeing it through.

Most people are utterly terrible at this not because this is an innately hard thing to do, but because the very idea of being responsible for defining your own process for accomplishing something is so beyond the average person’s world view they can’t even fathom having to do it.

Become Responsible for Our Own Structure

That’s the first part of your mindset that has to shift: You. Are. Responsible. For. Your. Work. It’s not your manager’s job. It’s not the CEO’s job. It’s not the job of the other people working on your team. It’s yours.

An example. Suppose you’re hired to run a brand new marketing concept at a company and you have total control over how every aspect of it can be done. You’re given a set of goals by your manager (that is their job) and some parameters on how the marketing experience should be delivered to the customers. Your goal is: increase profit by N %. Pretty unambiguous.

What I would do in this situation: review what the company has tried historically in this area, analyze the marketing copy and ads, game out a business process for quantifying returns on a new campaign, and float some test campaigns immediately. Assuming that I didn’t have to deal with an obnoxious procurement department or comptroller I’d have a live and running campaign deployed within my first five days on the job.

The distribution of research to action in week 1 of the job should be for every two hours I spend researching I spend six actually doing something.

What the many people do: fucking panic. Constantly seek reassurance; over-research the problem2; endlessly pursue fake work; and when pressed for results feign ignorance and play dumb. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing!” Bullshit! Your job is to increase profit! Sell more, cost less! It’s basic math!

The difference between the cases in this example is I created my own structure for attacking the problem. I know there’s a ton of stuff I don’t know; I can learn it. I’m also pretty sure there’s a bunch of unknowns no one in our organization knows. I can’t do anything about that so I’m going to experiment and gather data methodically to help determine them.

This is where we must begin - we have to create the system for our work and invent structure where there was none before.

Favor Direct Action over Passive Research by Default

A good rule of thumb for creating structure and systems: always favor direction action by default. We need to build our confidence and awareness up in order to deal with big, unknown problems resolutely; there’s no substitute for first-hand experience.

In the previous example, rather than spend our first week on the job watching a PluralSight course on modern advertising, let’s design a really simple test campaign with a small trial budget and get it up ASAP. We’ll learn a ton in the process and we’ll have results we can share with our team immediately. No one will care if our first campaign (or project or whatever) isn’t a success - the fact that we actually did something on our own initiative already puts us ahead of most.

Passive research such as taking a course, reading a book, and so forth are still worth doing. But you need to do those on your own time (unless it’s your company running the training.) You are still expected to produce even if you have to close a knowledge gap at the same time. This is part of the price of admission for working on exciting and big projects.

The big benefit of direction action is that it is productive and instructive at the same time. You form first-hand experience around the problem and have output to show for it. Never discount the value of social proof and demonstrable output in any human organization; a basic demo or a small completed project counts for a hell of a lot more than “I read a book!” does.

However, you can also turn the exercise of reading a book or other forms of passive research into direction action too if your attitude is so inclined. Show up to your team meeting with a presentation based on what you learned. Share your experience with the team and help them learn too. But can you spot the difference there? Reading a book in your cubicle and hoping to silently get started on some project without interacting or sharing with your team is essentially “hiding” from your work. It’s the knowledge worker equivalent of trying to run out the clock. Reading a book and sharing what you’ve discovered with your team is leadership.

Learn How to Create and Define Processes

Thus far we’ve:

- Accepted responsibility for our work and have chosen to create our own structure and

- Have made the explicit choice to prefer output-producing forms of learning.

The next step is learning how to actually build a system around our work. The takes two things:

- Being able to fit the entire problem space into your head at one time. This means avoiding rat-holing on specific details. You need to design a structure the aligns all of the output you and others in the direction of the same goal, is measurable, and able to be broken down into smaller parts and sequenced into a schedule.

- Define repeatable processes that are capable of being measured and sequenced for executing specific workflows.

I’ll give you a good example: debugging a hard race condition in the network layer of Akka.NET. The reason I’m pretty good at debugging these is because I’ve honed a repeatable approach to doing this over the years.

I begin by reading through the bug report or the failed test and try to form a picture of what all is happening in my head. Usually I’ll draw a sequence diagram showing what should be happening vs. what is actually happening. Then I’ll form some ideas about what is or isn’t happening and build a definitive set of theories that I need to disprove one by one.

This is how you “fit the problem” into your head at once: with structure and definition. From there, I move onto defining a methodology: process of elimination. This is going to be my system for determining the cause and existence of the error. If I have a team working with me I can assign one hypothesis to each team member and have them work in parallel with me.

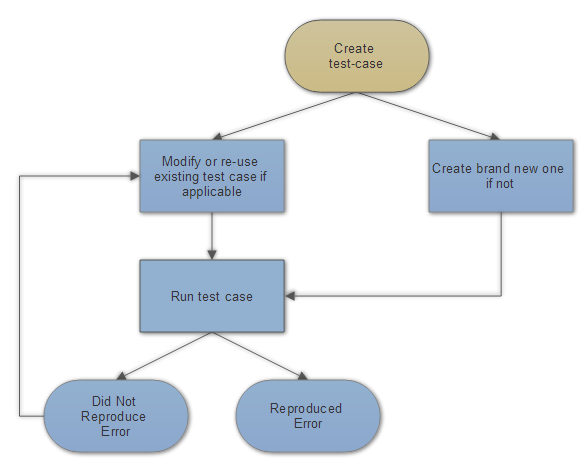

Next step is defining repeatable, reusable processes. I typically use a flowchart3.

Nothing too complicated about this process, but what it does is gives me a reusable tool I can use each time I have to approach a problem. This process above is just merely trying to reproduce the problem; I have others I use for tracking down the code, fixing the problem, and verifying the fix.

If you don’t invest the time into doing this, you will treat every single task as a one-off. Every new thing you do will be stressful. You will be a low output producer. And you will not succeed in your job. Systematic thinking and ability to invent structure is a necessary ingredient for success in any field.

Wrapping Up

If you build systems around your work you can methodically add structure to ambiguous (ambitious) problems and take something from being an unknowable, complex, and intimidating project to something that is workable and manageable.

There are freaks of nature out there, but most people simply can’t throw their intellect at a giant problem and hope to accomplish much of anything. Successful people work hard to break down big problems and work through them methodically. Start by looking at your own routines for handling your every day work and see where you could make an improvement there using these steps.

This process requires you to take ownership of your work and play the lead role in it. But if you can get this down there’s nothing you can’t do with a bit of time, measurement, and trial-and-error.

Footnotes

- A corollary to this law: the amount of reward you receive is directly correlated to your ability to deliver upon said responsibilities. If that’s not been your experience… Consider quitting?

- See the section on “analysis paralysis” here for further explanation.

- Seriously, invest in a good piece of diagramming application. I use SmartDraw for all of my diagrams. But there are loads of others. They’re in invaluable in helping you define structure around your work.